I was fortunate to attend the 30th anniversary Pareto Conference held in Oslo last week. Its been several years since I last attended and I looked forward to an unusual gathering that brings together a big part of the O&G value chain. Whilst I am an “upstream” guy, I have always valued this conference for the window into the wider industry that it provides. This year was no exception.

Unsurprisingly, the atmosphere was much more up-beat than recent years. Its amazing what $90 Brent can do for everyone’s mood. That said, there was no euphoria, and indeed the theme of this note is that most dangerous of sentiments: “this time it’s different”!

For many companies in drilling, oil-field-services, upstream and tankers the common theme was the same – despite higher revenues, uncertainty and rising costs are combining such that companies shun growth and harvest cash. This is short-term good for investors, but raises a more existential question about the industry as a whole. If no one is re-investing, what happens 5 or 10 years down the line?

Drill Baby, Drill (but don’t build)

In this note I will focus on the big drilling companies – and specially those that focus on the “floaters”; semi-subs and drill-ships. These are the royalty of drilling, with very high-tech rigs enabling the oil companies to push the frontiers of oil exploration and production out into deeper waters and harsher environments.

Having suffered through the 2014 oil price crash and the subsequent lean-years, demand for rigs is picking up and day-rates they can charge increase with the overall fleet utilization rate. Of note, the day-rates tend to go exponential once utilization is above 90% (a squeeze), and we are not there yet. This trend is typical of the oil boom-and-bust cycle – which usually leads to a frenzy of debt-fuelled new orders and a subsequent collapse as too many new rigs enter the market. In the previous market, the travails of KCA Deutag and Sete Brazil are well known

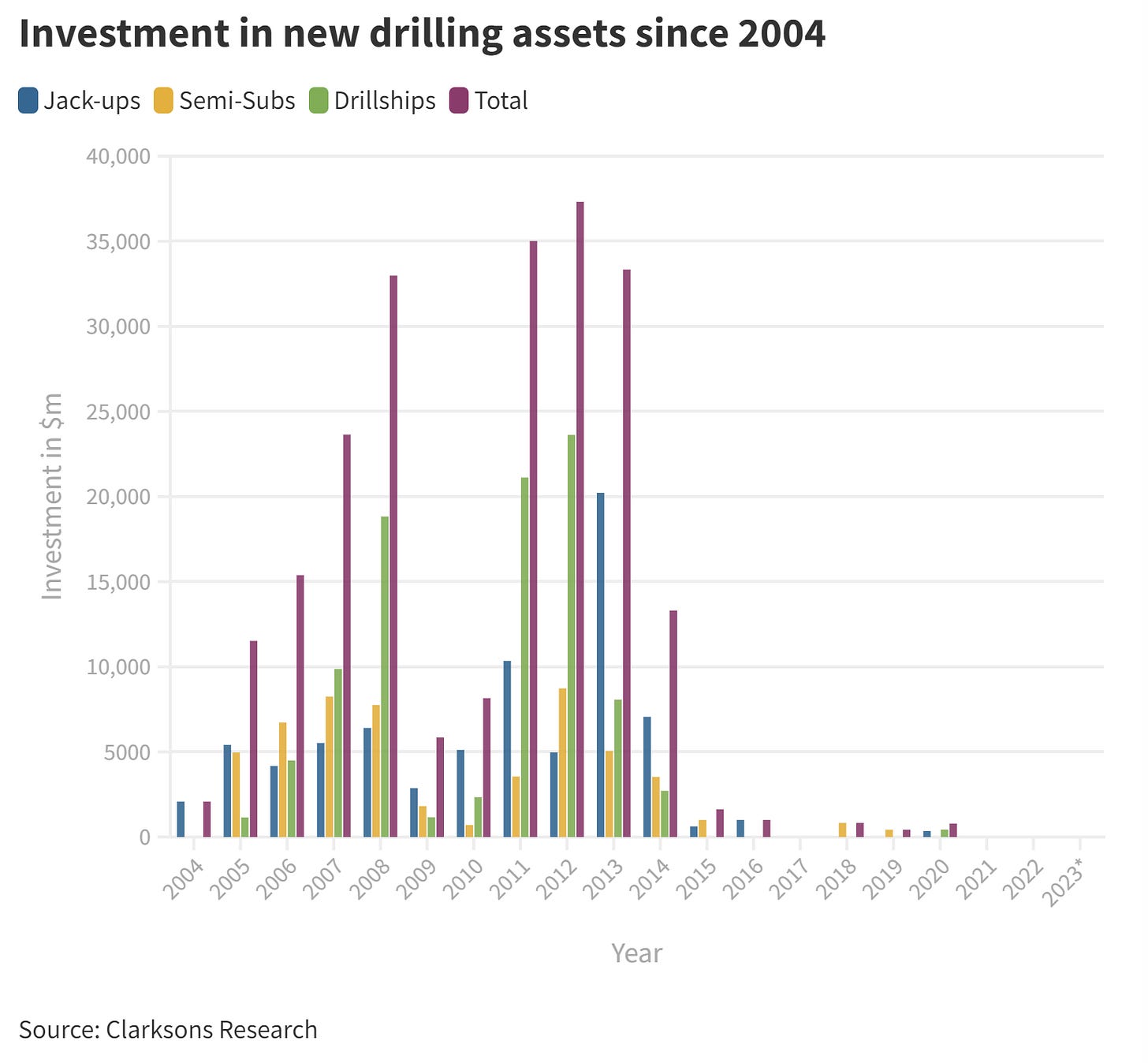

Where it is “different this time” is that not one of the companies is talking about ordering new rigs/ships. It’s not hard to see why:

the new-build cost is extremely high (circa $1bn),

cost-of-capital is high for everybody, and more so for the defunded O&G sector,

delivery would be 2027 or beyond (if you can find a shipyard) and

most importantly the value assigned to a new rig would be about 33% of the cost – so any new order would be seen as a liability and could tank the share-price.

A casual remark suggested they would need “$650k/day rates” (currently $450k) and “visibility over 10-15 years of contracted use” to justify a new-build.

It’s not happening. and this is just continuing a trend that started with the 2014 oil price crash

This mismatch between the carrying value of existing fleet and a new build is clearly driving the reticence to place orders - an order would be a liability not an asset with respect to a company’s share-price. A second conclusion one could draw is that it could be cheaper to buy companies with existing fleets than to order new rigs. Consolidation ahead?1

Harvest Time

The result is big companies are running their fleets for cash. After years of famine come years of plenty - allowing for deleveraging, re-building war-chests and returning cash to shareholders. The new motto must be “Carpe Diem”.

As noted in the introduction, this is good for shareholders, possibly very good2. But when stepping back and looking at the industry as a whole, taking a longer time-frame, we can see that this is unsustainable. Happily, rigs fleets in the floater segment of the market are generally very young - the recent severe downturns lead to a lot of scrapping of rigs - this is the brutal reality of supply-demand economics.

For a company managing increasing demand, with a relatively young fleet, the immediate future is even higher day rates and utilization - which go straight to the bottom line. Run this out several years, with no new Capex - no new orders, and we can see just how cash generative these businesses will be.

Roll the clock forward a bit further and we can start to see the problem - the fleet ages, demand remains high and prices rise until there is demand destruction - the point at which Big Oil can no longer afford to contract rigs. This means fewer wells - indeed when we look at “investment dollars” into the E&P space we know the total amount is declining, but here we can see that there will be even less getting done as costs inflate.

If OPEC+ succeed in maintaining prices north of $70, we would expect increased activity (albeit far from boom-times). AT what point will we see exploration constrained by lack of affordable rigs?

There is probably some scope for getting a few rigs out of cold-stack, but the costs of this can be equivalent to new-builds in the worst case.

Beyond the Event Horizon

Beyond this - what of the business model for the Drilling companies? Harvesting cash, rebuilding the balance-sheet, and returning cash to shareholders is OK for a while, but much like an oil company with a depleting oil-field, the end game is net-zero assets.

The question I was left with is “what has to happen for drilling companies to return to ordering new-builds?”.

I don’t have an answer to this, but if/when it does happen, will there even be any shipyards capable of diving back into the rig business?

In the meantime, we may well see NOCs being the only clients for new-builds - something that could continue the trend of reducing Big Oil’s footprint.

“This time it’s different” is usually proven wrong in short-order, but in this case I can’t see any return to the build-bust cycles of the past in the heavy-metal sector.

Clearly, this is amateur speculation and most definitely not investment advise of any kind.

yep, again this is not investment advice…

Go long drilling since they have a developing, unintentional monopoly/oligopoly? Could be an investment thesis. :)