“Scotland can become the Saudi Arabia of renewable power” - a great soundbite , Alex Salmon in 2011 and “UK can be 'Saudi Arabia of wind power' “ BoJo in 2020.

There are undoubtedly many other examples of this kind of platitudinous feel-good appeal-to-emotion: California, Texas, Spain, Australia take your pick. But let’s stop and ask why this comparison? Why Saudi Arabia? After all it is not exactly a bastion of liberal “Western” values (that said, intolerant authoritarianism does seem worryingly appealing to many in the liberal-green-left).

No, the metaphor of “The Saudi Arabia of Renewables” is used because it alludes to the immense wealth and influence of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA). Spoiler alert - this wealth and influence is a fluke of geology and a construct of modern geopolitics - with KSA having an outsized role as the largest exporter and often the swing-producer in the world’s unabated thirst for oil.

Likewise, super-wealthy Norway is held-up as an example of how the “green transition” can happen - with nary a nod to this being a function of its vast oil and gas derived wealth.

It may seem an odd question – but what is the connection between naturally occurring oil and gas reserves and state wealth?

In a future post in this series on money, energy and economics I will delve more into why surplus energy is the economy. For the sake if this post I’ll take a shortcut.

Petrodollar Hegemony

Churchill saw the significant advantage that oil’s energy density could give the British Navy as early as 1911. So great was the advantage, that Britain swapped out security of supply (the UK has large coal reserves) for dependence on imported oil. The significance was underlined by the Second World War - with oil playing a major role. ( In 2017 I wrote about the role of oil in the WW2, here)

Similarly, despite having massively increased its domestic production during WWII, the USA recognized the need for increased security of supply. In 1945 FD Roosevelt signed an agreement with King Abdul Aziz Ibn Saud on board the USS Quincy on the Great Bitter Lake in Saudi Arabia - this was essentially an oil-for-defence agreement. (The Adam Curtis film “Bitter Lake” is a good but winding and over-long recounting of the legacy of this agreement).

“More important, in a sense, for the long-term was the U.S. belief that oil scarcity was always on the horizon, and could really only be mediated by the gigantic and cheaply extracted reserves under the Saudi desert." (history.com)

let’s focus in on that…. —> “gigantic and cheaply extracted”

Oil and gas are energy dense - you get lots of bang-for-your-buck - you get a huge amount of work for very little cost. Energy is the ability to do work. One can consider the calorific value of a barrel of oil, which is something like 5.8 million British Thermal Units (“BTU”), and then compare this to how much work a fit human can do in say an 8hr shift 5 days a week. There are various attempts at this - but generally you end up with estimates of many years of human labour being replaced by 1 barrel of oil energy. Or more realistically - human labour is leveraged by this additional energy.

As for the cost, $100/bbl oil may sound expensive, but when you multiply the number out (8hrs * 5 days/w * 52w/y * X years) * minimum wage - you can get to silly numbers like $150,000/barrel of oil equivalent. Side note - this analysis usually ignores the energy losses in converting heat energy into work - but even if we apply a 35% efficiency to focus on exergy, the value of energy dense oil is still a couple of orders of magnitude above the cost.

The difference between oil at $90/bbl and the work it provides ($50,000/bbl labour equivalent, if we use 33% efficiency) is what makes oil massively valuable to society. It is so cheap that we can ignore it in economic models - and unfortunately become blind to the value.

Herewith the aforementioned short-cut:

when money is simply a call on energy, using tiny amounts of energy (or by proxy, money) to access naturally occurring energy resources is the antithesis of a subsistence. This is “surplus energy”; the “free” energy that you get above-and-beyond what you invested which can be used to do huge amounts of work. Getting things done for free is a definition of prosperity and wealth.

For countries endowed with vast natural resources there is an easy win. It is reported that in the early days of production from the relatively easy onshore fields of the Middle East - the cost of extraction was about $5/bbl.

The rest of the world is “happy” to pay $90/bbl knowing that they get vast amounts of work for that paltry $90. The difference between the lifting cost and the sales price is basically the profit margin for the producing country. Given this it is unsurprising that countries that export lots of oil, gas or coal are generally rich. There are exceptions, but those usually comes down to corruption and mismanagement, state-capture and kleptocratic looting.

Clearly it is not as simple as this - as there are exploration, development, transport costs etc. But the bottom line is that typically for a country that holds natural resources there is a massive margin between cost and price.

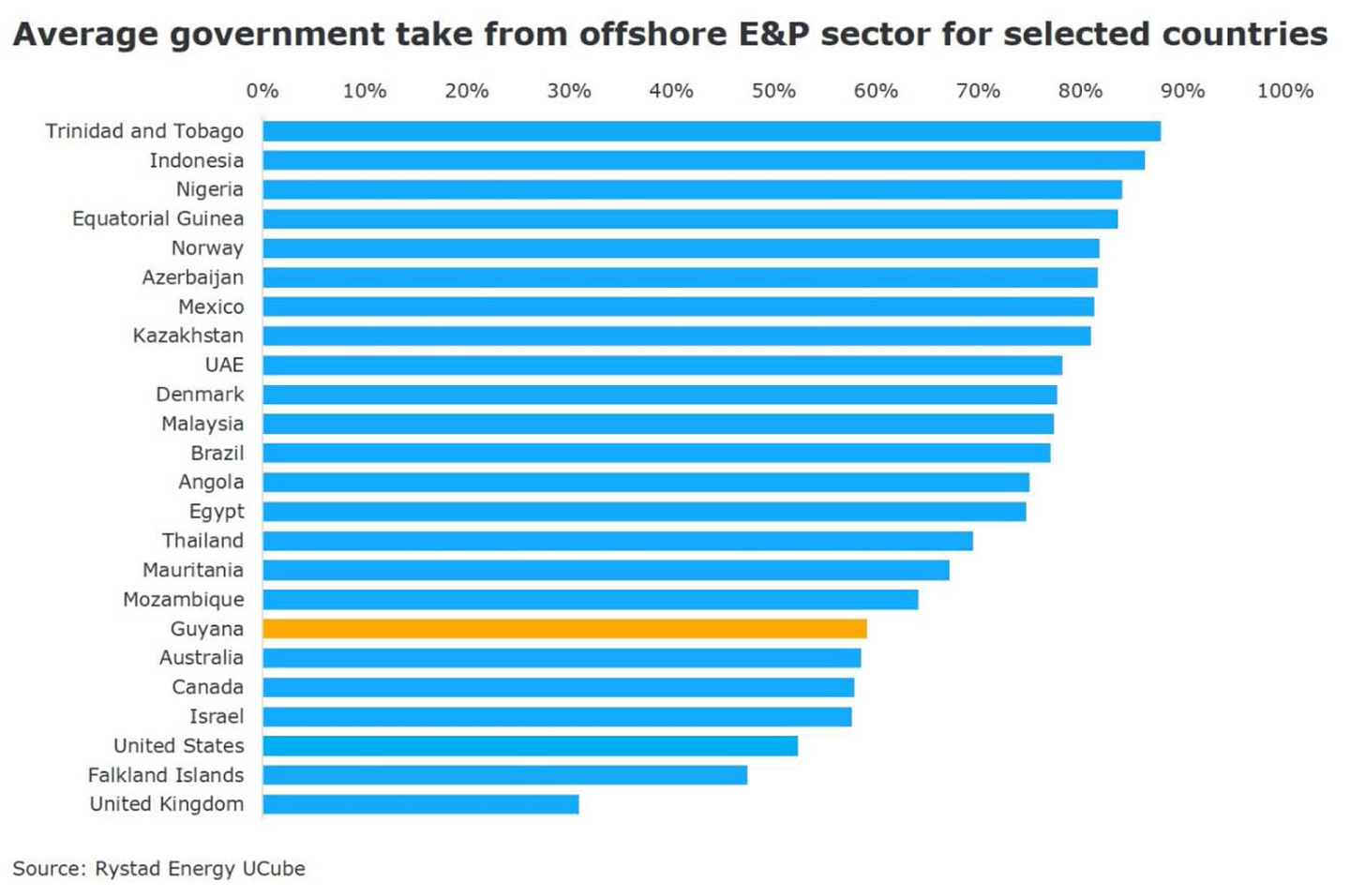

For the much hated Big Oil - the margins are much smaller - simply because most countries extract significant taxes and/or royalties - so that the value of the nation’s resources (rightly) stays with the nation, not with the oil company who are basically providing a service. Forget the “Fossil Fuel subsidies” headlines. Tax rates can be 85%.

We will know that Wind and/or Solar have hit the big time, not by breathless headlines about installed capacity or % growth, but by when these systems provide both electricity and tax revenues.

In general, petroleum taxation is different from normal business tax because companies are exploiting a natural resource that belongs to the country - hence the host country extracts tax in various forms, whether as taxes or as royalties, or in the case of state-owned enterprises, the company coffers and the state coffers are often fungible. If we stick with Norway, it has a high petroleum tax with a “government take” of something like 80%, which is not unusual. You may hear about how O&G get subsidies, and whilst this is a separate discussion, its worth noting that often this outrage is that some of this extra-ordinarily high taxation can be recovered against certain losses. In the case of Norway, cost of exploration wells (even if dry) can be mostly recovered - this is an incentive to explore, but not a subsidy per se.

Many countries use this windfall revenue stream to fund their social programs. The UK can wonder where its Sovereign Wealth Fund might be had the not all these revenues gone into funding the deindustrialization transition since Thatcher (oddly, the revenues show up in inflated real-estate values in the UK - but that really is a different story).

Norway with a small population and a huge tax/royalty income has saved some US$400bn, which after wise investments is now worth north of US$1000Bn. Alaska has cut checks to its entire population for years thanks to its oil revenues.

Saudi Arabia has a smaller SWF than Norway - and whilst this may be surprising, it is because more is simply spent on the the operating costs of the country as well as large capital intensive projects at home and abroad. In addition, large portions are likely held as overseas investments - so its hard to gauge the real wealth of KSA. Suffice to say it is not poor, having the 18th largest economy in the world and a Per Capita income of about US45k.

Headwinds

In the mythical world of the Green Energy Transition - swapping fossil fuels for renewables will be “profitable” - it will create millions of well paid jobs and create cheaper energy. This has been described as the kind of wishful thinking you find in the Broken Window Fallacy. In this economic theory, you could have people break windows which would spur economic activity in replacing broken windows - a “win” for economic activity. Of course this fails to account for the “unseen” cost which is that capital employed in fixing broken windows is not available for more rational (and more productive) uses. There is an illusion of economic activity.

How will we know whether a renewable energy powered economy is possible? I don’t hide my view that this is entirely unrealistic - but putting my opinion to one side - one could suggest that we will know that renewable energy is replacing fossil fuels when modern industrial societies can be sustainably powered. Indeed, if the promises are valid, one would expect that renewable energy should be value creative - just like oil is for KSA and gas is for Qatar.

So when a politician says that their corner of the world will be “the Saudi Arabia of Renewable Power” they are living a fantasy. The oil that is produced cheaply in Saudi Arabia does three things

It provides all the energy needed for Saudi society (directly or via revenues)

It provides all the energy needed to sustain production of oil into the future

It provides massive income for the country

The hidden contribution to global prosperity is that all this cheap/almost free energy allows the rest of the world to make stuff and trade - creating the positive growth loop that allows other countries to buy the oil and gas products.

Whilst it is still early days in the supposed “Energy Transition” we have to ask NOT simply whether renewable energy is able to power the economy, but also:

will it be able to provide all the energy needed to ensure sustainable (i.e. build the second generation of harvesting machines)?

can it provide reliable energy cheaply enough to enable global manufacturing and trade?

can it provide tax/royalties for host countries?

Clearly there is a long way to go between having some energy provided by renewables and anywhere becoming a “Saudi Arabia of Renewable energy”.

Indeed, the low energy density and the low Energy Return on Energy Invested of renewables would suggest that we will never see a “Saudi Arabia of Renewable energy”. In the meantime, just to get to the first step of (partially) powering a modern economy, open-ended subsidies are still needed.

Post Script:

To keep this post to a reasonable length - a couple of asides on subjects core but not covered.

(1) The cheapness of oil and gas (and coal) and the consequent positive impacts on the global economy are ignored in economic theory - but it is a valid criticism that negative externalities are not expressed in the price/cost of hydrocarbons. It is unreasonable to focus on the negative externalities yet ignore the positives.

(2) One can imagine that using current relatively cheap fossil-fuels to do a massive build-out of nuclear power could break the cycle of reliance on hydrocarbons - the energy density is huge as is the EROEI (although this is very hard to quantify).

Great article Richard. You could add to the importance of oil, as witnessed by its relatively high ERoEI but also by its “storablility” and “transportability”.

Renewable sourced electricity is a high quality energy but electricity cannot be stored in meaningful quantities. It must be converted to potential energy (pumped hydro), chemical energy (batteries or hydrogen) or heat energy (heat storage) with large round trip energy losses.

Oil and coal are easily stored in tanks and heaps and oil is easily transportable in tankers and your car petrol tank.

Direct access to electricity requires physical connection to wires or rails.

Great article once again