Outside of the oil and gas bubble, Guyana is little known. I would guess that most people wouldn’t even correctly guess the continent, let alone an exact location. This anonymity is starting to change; recently given a viral boost by the train-wreck interview with President Dr. Irfaan Ali of Guyana ( a “train wreck”, that is, for BBC Hard Talk’s Stephen Sackur).

Long before this internet event, Guyana had been gaining fame as one of the hottest hotspots for global oil exploration. Whilst some mavericks had long been enamoured with the potential of Guyana as a frontier oil play, everything changed in 2015 when Exxon made their first discovery. Incredibly, first-oil was produced only four years later in 2019 and Exxon and partners have made a string of discoveries. Estimates vary, but figures north of 11 billion barrels recoverable are often quoted.

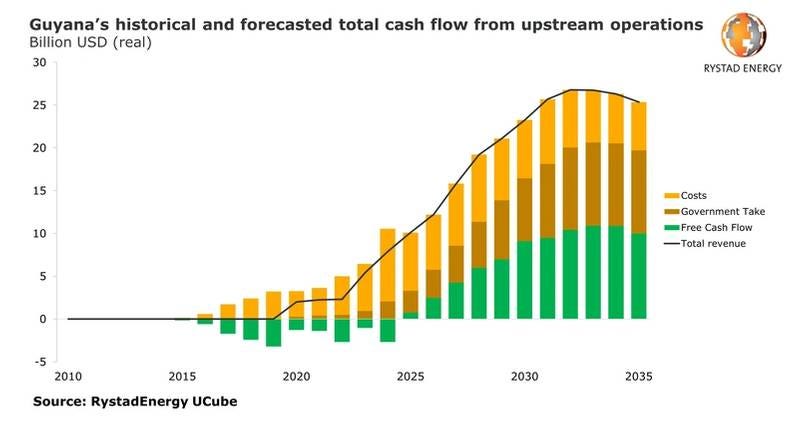

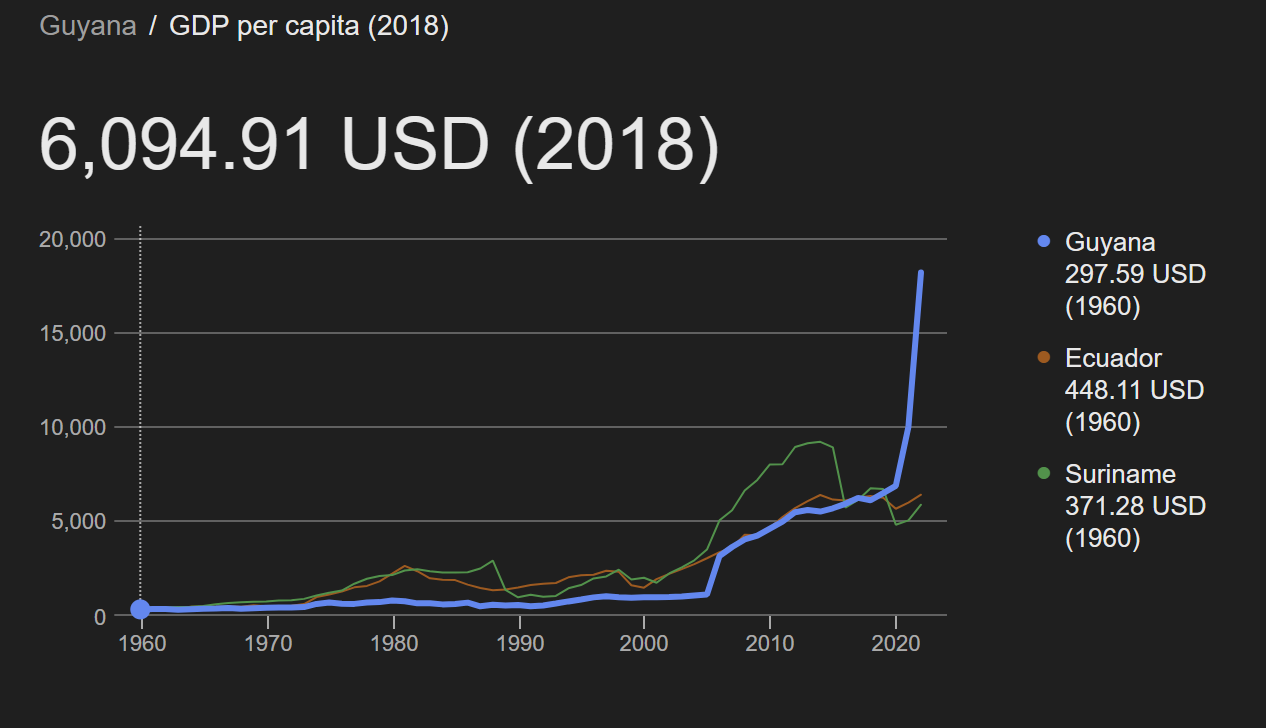

Quite quickly, people noted that Guyana has a population of about 800,000 - so this kind of oil wealth is extremely significant for the country. From a standing start in 2019, it is estimated that production will reach 1.2mmbbls/day by 2030. This translates to $10 billion annual revenue to the government - which can be contrasted to pre-oil revenue of a few hundred million and a GDP (i.e. the entire economy of Guyana) which was only $4.8Bn in 2018.

For good reason the “New Kuwait” epithet been applied. This is no idle comparison. Kuwait has about 10bn bbls of reserves (and of course a long history of production), a relatively small population (4.7 million, so significantly larger than Guyana). It is also famous for being a very wealthy petro-state, with GDP in 2018 estimated at about $140bn, with 50% being attributed to the oil and gas industry (and 90% of its export earnings and fiscal revenues).

In this world, everything we have has either been grown, mined or manufactured. Kuwait (along with most petro-states) has sought to diversify its economy, but notwithstanding this it is clear that most of its wealth comes from oil. Guyana is likely to be even more extreme. The great danger, of course, is the “resource curse” - in which rapid exploitation of natural resources leads to inflation and crushes all other parts of the economy. This is not the subject of this post, but we hope that Guyana is well advised and manages the transition.

Risk vs Reward

At the same time, it is quite clear that Exxon and partners will be making a ton of money from this (the green bit “free cash flow” in the Rystad chart, above). And there are the expected and usual noises about reviewing the fiscal terms that govern the way in which oil revenues are shared. The linked article reflects a refreshingly rational viewpoint from the Attorney General of Guyana. The problem of course is that pre-discovery, any frontier nation has to attract investors. How to convince someone to come and buy a $100m or $200m lottery ticket? (exploration wells are expensive and by O&G folk-law have a 1/10 chance of success). The only way to do this is make the prize big - you can’t change the geology but you can make the fiscal terms attractive such that if the exploration is a success the risk-taking investor can see a clear path to outsized returns.

When the fiscal terms are viewed post-discovery, it is easy to be critical and suggest that the nation’s riches have been “given away”. The worst solution is to change the contract terms retroactively - this alienates all future investors - although some jurisdictions get away with it if the geology is sufficiently attractive to allow investors to swallow this massive political risk. The better way is to accept the reality (and honour the contracts) and ratchet the fiscals such that subsequent licenses have much more onerous terms (i.e. favourable to the host nation). This is reasonable as the geology has largely been de-risked, so the rewards for the investors should be lesser. It is no accident that prolific oil provinces have punitive fiscal terms - tax rates up to 85% (Angola), 78.004% (Norway - and no, I have no idea why it has the decimal oddity).

The point of this?

Subsidizing, not Subsidies.

For sure, Exxon (and partners) have favourable fiscal terms and will make a lot of money, but they took significant risk doing frontier exploration. Guyana will benefit enormously from the windfall that will come from the development of their oil deposits. How they manage the economy is a separate conversation.

It would be good to contrast Guyana to a small country somewhere that had rolled out wind and solar. In theory, wind and sun provide the cheapest electricity - in practice of course this is only true if you narrow your definition to point-in-time generation. Now there are breathless articles about numerous countries that have 100% (or close) renewable electricity. However, the success stories of wind and solar are absent, with all the top countries in these lists being dominated by hydro and geothermal sources.

What would be great would be to see some evidence of the “Saudi Arabia of wind power” or even the “Guyana of solar”. As I have pointed out before, the aspiration to be the “Saudi Arabia of [blank]” is a reflection of the fact that Saudi Arabia is enormously wealthy thanks to its oil resources. (In some parts of the overly zealous western democracies there may also be a degree of envy of the autocratic top-down management that KSA has, but that’s a different story.)

The lesson from Guyana is that the exploitation of natural resources can literally power the economy. This is in stark contrast to renewables which also exploit the naturally occurring wind and sun, but need indirect (and usually, direct) subsidies AND the current trend is to need bigger and bigger subsidies.

Bang for your Buck

The coming-of-age for wind and solar will be when they can not only stand on their own two feet (so to speak) without subsidies, but can also contribute tax and royalties to the host country in meaningful amounts.

I am sure that in the minds of many, the Greener, Cleaner and Cheaper future will indeed have an economy super-powered by renewables alone. I am convinced this is impossible: the reason is you get so little energy out vs. what is used in the harvesting. It’s not negative for sure, but nowhere near the level needed to liberate society from the shackles of energy gathering. The “bang for your buck” just isn’t big enough, or in terms many will recognize, the EROEI is too low.

I would love to be wrong, but I don’t think we are seeing any economy having a steroid hit like Guyana thanks to renewables, indeed we are seeing the opposite as metastable economies start to wobble.

This is a huge topic and one that many can intuit, but is always drowned out by the cacophany of (very well-funded) advocates for the “transition”. If renewables can’t contribute meaningfully to the wealth of countries we have to think about what the consequences might look like. Stay tuned.

Great article, as usual. I do hope Guyana manages to avoid the pitfalls of Petro statehood. I have never been there, but my parents had a friend, back in the day, who originated from there so I used to hear about the place a lot. I appreciate that you emphasize the nature of investment risk, that in this case Exxon took the risk, and got a high payback. Too many people today (the general public) seem completely unaware that all enterprise includes risk, and resulting profit is one of the incentives to take that risk, and in the end, makes us all richer. And lots and lots of risk takers also lose their shirt.

The larger fight on the horizon, at least in the US, is going to be the tech industry versus the climate lobby. The amount of power needed to power data centers and artificial intelligence is exponentially higher than most people believe and will continue to grow. It bolsters your argument that in any real growing economy, wind and solar cannot cut it since they are not energy dense and are not dispatchable.

Good article. Thanks for the info.