Slings and Arrows of Outrageous Fortune

Protesting against fossil fuels may make one feel virtuous, but the consequences will be felt for a generation

Last summer in France, over a very agreeable dinner on a warm summer evening, a good friend said he read my posts on Linkedin and he wondered why I was “so angry”. I was surprised – I didn’t think I was angry, and I try to be balanced and well researched in my writing. Anger was not top-of-mind as I wrote. I was taken aback because I didn’t think of myself as angry.

But like good food, good observations need a bit of digestion – and having ruminated on this I think he was right. I am angry.

What we see in polarized social-media is that there is deep anger – most of it born out of a widespread and deeply held view that we are on an inevitable path to climate apocalypse – perhaps best personified by the placard “you’ll die of old age, we’ll die of climate change”.

I’m willing to take a bet that both me and the person holding that placard will die of old age. But I’d also be willing to bet that our lifestyles and possibly even our lives will be curtailed by energy poverty long before climate change.

I am angry because I believe that decadal policies focused on long-term climate concerns have been (and are) driving our societies towards the cliff edge of an energy crisis. I believe that the energy crisis is a “clear and present danger”, and one that is significantly more imminent than anything climate related.

The riposte to any concern about the economy is that “there is no economy on a burning planet”, which is certainly true. But the truth of this statement does not exclude another truth: that is that there is no climate response with society in collapse – unless, of course, you secretly think that millions dying IS the way to solve climate change. Not only is there no response, but our resilience to natural disasters, our ability to adapt, will be absent in the absence of wealth.

Despite the emotional response to “natural energy”, people have never lived in harmony with nature, people died in harmony with nature. Cheap and abundant energy has given us some degree of mastery over nature, albeit at a cost to ecosystems.

When you have started to see the world through the lens of energy, it is impossible to “unsee” it. There is a lot of academic and blog-style writing on this subject – but almost none in the realm of mainstream economics, finance or politics. At least not in the West. I suspect that China with its long-term planning “gets it” a whole lot more than Boris or Biden, BBC or CBC.

We are currently in the “grip” of a commodity crisis – with inflation tearing at people’s wealth. Inflation is not a “domestic” problem, although it has been exacerbated by the printing of money (QE after the Great Financial Crisis, and the Covid response). Inflation has been caused by demand outpacing supply. Demand has been surging in a post-covid world – and specifically the expectation, ambrosia on the lips of activists, that the world had changed thanks to Covid – demand would never come back, we had achieved Peak Demand. This wishful thinking led to much surprise and headlines of the “unexpected rebound” from people who should have known better (IEA - looking at you – you know the meme “you only had one job” ?)

With demand surging we have been hit with a second whammy – the focus of activists, media and politicians on supply destruction in the hope that this will boost the energy transition. Ironically (or maybe not) boosting the transition may be the outcome. The only caveat is that massively higher energy prices, and an impoverishment of large sections of society was never mentioned in the promise of the sunlit uplands. when you see the world through the lens of energy – as a system of energy not money, this was inevitable.

They say the definition of a tragedy is not that it is tragic, but it is in the inevitability of the tragic outcome.

Energy is not just your electricity, heating and petrol bills. The economy is the sum of millions of transactions and transformations – every one of which needs energy as an input. We take resources, we make stuff, and we throw stuff away – that is the economy. Energy is the economy – to talk about “energy and the economy is a tautology” (V Smil). Look around you – everything has either been grown or mined. Everything. Food production is a form of primary energy generation (not ironically based on solar power).

The cost of “stuff” is increasing – that’s inflation – and we are going to start to understand what is essential and what is discretionary. The markets have already started to get this as investors cycle out of “growth” stocks into “real assets”. As the cost of essentials increases, so there is less money to be spent on discretionary things. I am in my mid-fifties, and yet I am too young to really remember the last time we had serious inflation. Inflation is going to be a shock to the system. I have seen inflation – in Venezuela in 1994, with the devaluation of the Argentine Peso in January 2002 and in Angola in the mid-1990s, but in each case, I was just a spectator insulated by hard currency from the pain. For those who live it, it is brutal and requires a different set of skills; something we in the “West” have lost. One friend suggested that if you have a world view that economic collapse is possible and possibly imminent – one would be better off living in a country that already has these problems – because people have coping mechanisms. Food for thought so to speak.

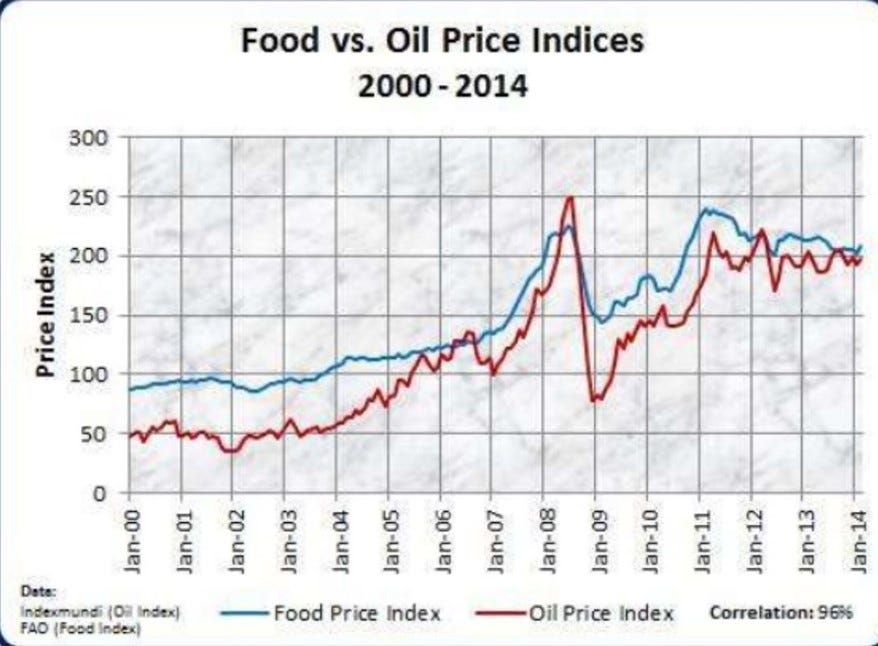

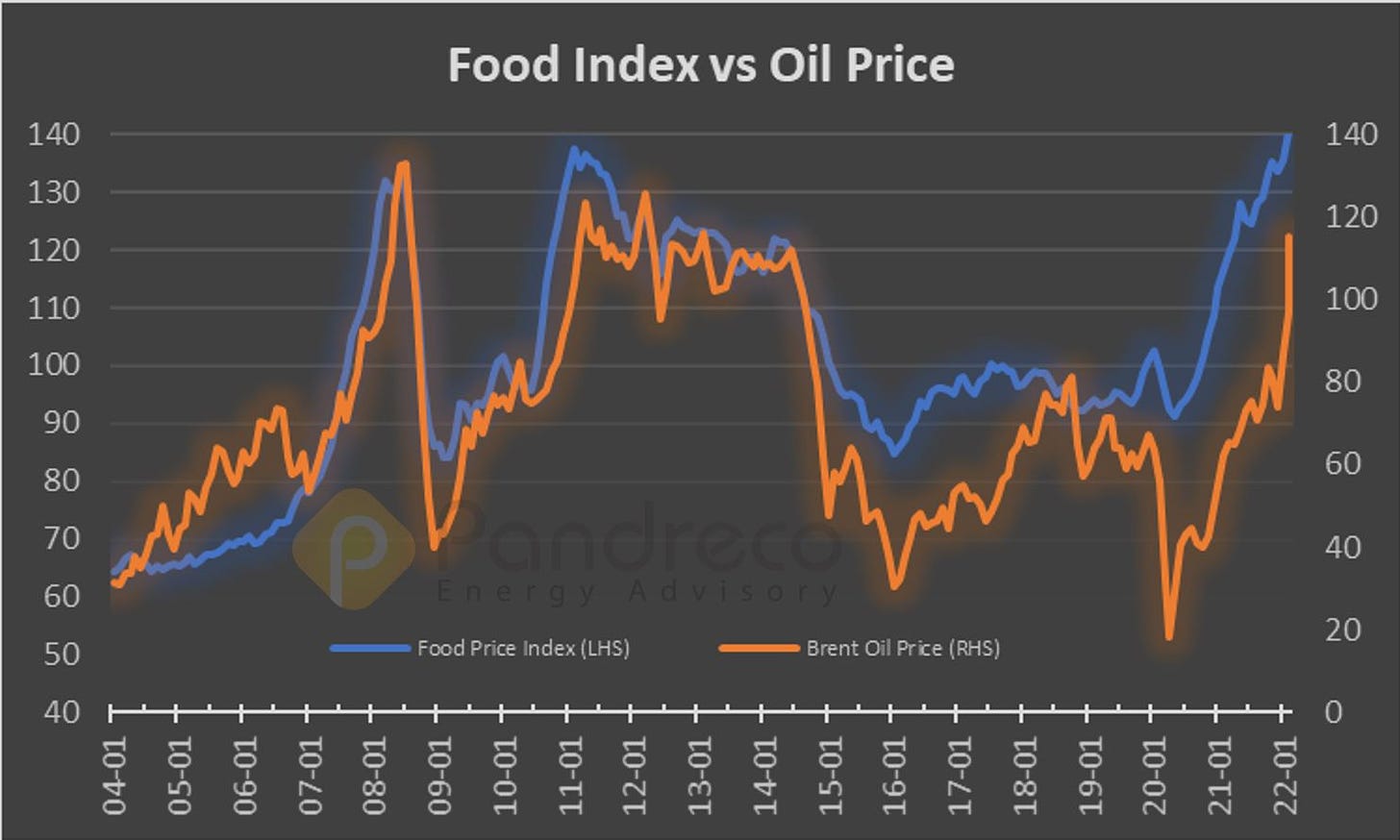

Perhaps the biggest threat to global security isn’t the price of gas for heating and electricity, and/or oil for transport (although these are significant), but it is the threat to food supply. For many years I have used a chart that plotted world Food Price Index against the Oil Price – and the correlation is shocking.

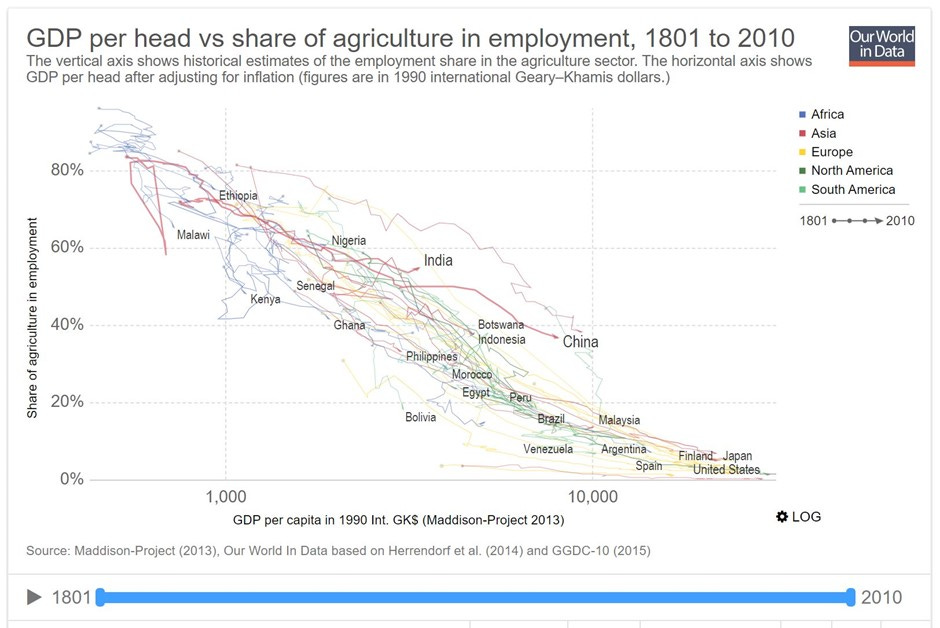

As the saying has it, “when you eat a potato, you are eating oil”. This is because modern farming is massively mechanized – almost nobody in OECD countries actually works in farming.

Despite a tiny fraction of the population working in food production, countries like the US and Canada are net exporters of foods.

Foods need to be farmed, processed, transported, usually refrigerated, processed and got to retail – all of which require energy – and specifically oil in the farming and transportation phases.

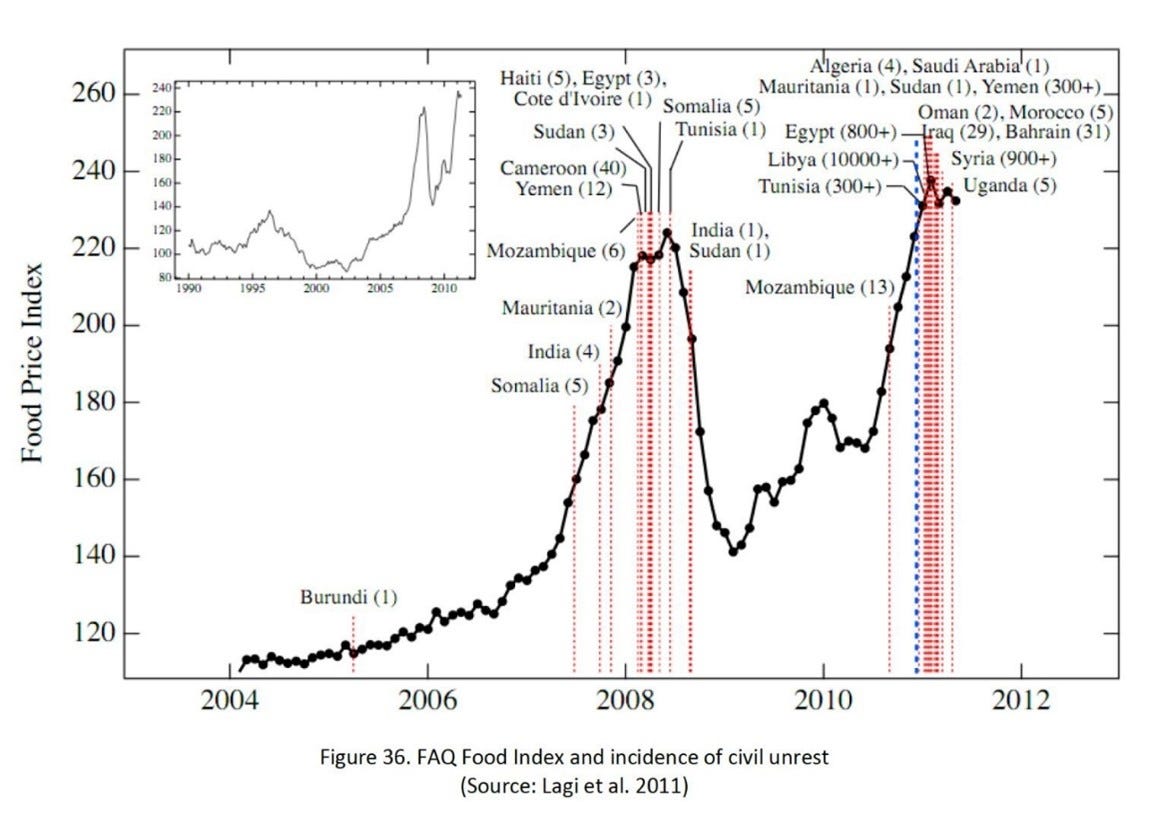

The Food Price Index might seem quite abstract, but it is put into stark context because there is a strong correlation with the FPI and civil strife and indeed wars.

The Arab Spring has been strongly associated with inflation in food and basic necessities.[1],[2] Although for balance it is worth noting there is also research showing many other contributing factors.[3]

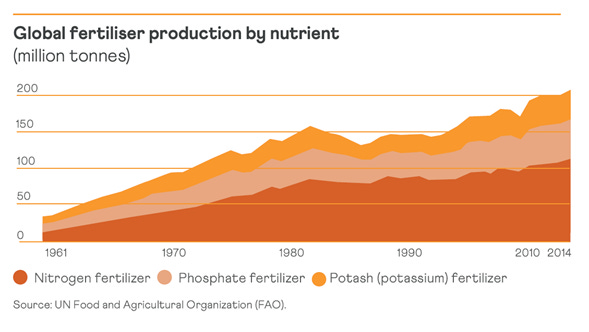

In addition to the overall process, modern farming requires significant amounts of fertilizer. Fertilizer that is made from natural gas represents almost half of the fertilizer used in the world (the rest is Potash and Phosphate, both “mined”).

It has been estimated that something like 3.5 billion people are fed as a direct result of nitrogen fertilizer made from natural gas, out of a global population of 7.6 billion.

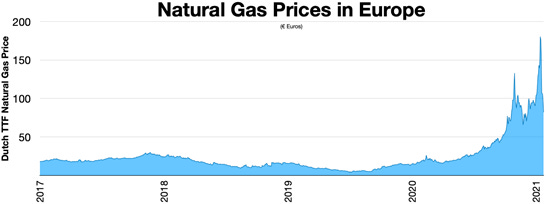

Now think about what has happened to gas prices recently. Relative to 2017-2018 this is a 3x increase, relative to 2019-20 it is more like 5x-10x. This has caused the shutdown of some fertilizer producers in Europe, and it doesn’t take much imagination to see increases in gas-prices —> increased fertilizer prices —> increased food prices.

After years of low natural gas prices (especially in the US thanks to fracing, and globally due to LNG), prices have increased massively – and it is critical to note that this started in August/September of 2021 – 6 months before the invasion of Ukraine.

It seems likely that the next step in this tragic chain is:

increases in gas-price —> increased fertilizer price —> increased food price —> increased “civil strife”.

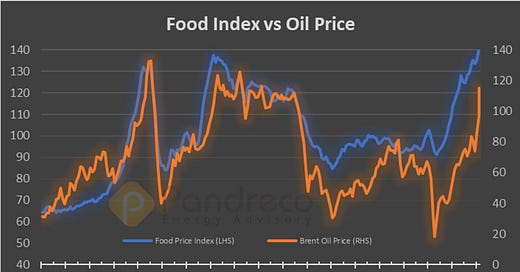

About two weeks ago, when preparing for a presentation I gave earlier this week, I went back to the data and updated the FPI vs Oil Price chart.

The correlation remains impressive – although note I have adjusted the scale of the FPI (LHS in blue) slightly to superpose the curves. I would point out two things from this graph:

1) The Food Price Index today is already above the levels in 2008 and 2011 that have been correlated with civil strife, and

2) There is no obvious end to inflation in oil and gas prices - so one would expect to see further increased in the FPI and a period of higher-for-longer prices. In addition to the underlying energy squeeze, the invasion of Ukraine will adversely affect global food prices due to the fact that both Ukraine and Russia are significant exporters of wheat (and other products).

We can also note that the FPI seems to lead the oil-price in several periods of rapid increase – I suspect this is an artifact of the data rather than a significant feature. The FPI data is from the UN Food and Agriculture Organization.[4]

Whilst headlines about “climate refugees” make for ideal click-bait (playing on both the fear of climate and the fear of refugees), if the supply of oil and gas remain depressed in the face of strong demand, we will likely see “energy refugees” in the very near future. Famine will occur, and undoubtedly climate-change will be cited, but the energy crisis will be there inconveniently for that narrative.

In some ways the war in Ukraine allows politicians in the West to blame higher prices on Putin - and be willfully blind to their own complicity. Activists and media and politicians (there is a theme emerging here) who demand the reduction of supply whilst being ignorant or disingenuous about demand have created this problem. I also believe there is enormous culpability with academics and populists who promote the "greener and cheaper" narrative. People genuinely believe this and act accordingly.

Greener but more expensive is the reality and this will make people poorer - may be in the long run this is a better outcome; but in the short term it will cause a lot of suffering. The pain of higher prices in rich countries will translate to shortages and famine in poorer countries – hardly the social/climate justice that is so easily promised in slogans and speeches.

What is needed is an honest conversation about the inevitable trade-offs; whilst ideology and dogma rule this is not possible.

The tragedy that is the current commodity and food crisis was predictable - that’s why I am angry. Sadly, this is not even the end of the beginning.

[1] https://www.pbs.org/newshour/world/world-july-dec11-food_09-07

[2] https://arxiv.org/pdf/1108.2455.pdf

[3] https://www.wilsoncenter.org/article/forecasting-instability-the-case-the-arab-spring-and-the-limitations-socioeconomic-data

[4] https://www.fao.org/worldfoodsituation/foodpricesindex/en/

Thanks Prince Richard. 2008, 2020, 2022 .. indeed we just started Act III of the play ...

Meanwhile looks like the West "took arms against a sea of rubles" :)