Are Net-Zero ambitions compatible with African development?

I wrote this as a guest article for Savannah Energy's 2022 Annual Report and is republished here with their kind permission.

Africa is home to 15% of the world’s population yet it’s share of cumulative global green-house gas emissions is tiny. It is inevitable that energy demand on the continent will increase through development, urbanization and population increase.

No country or region has developed without the extensive use of hydrocarbons – should Africa be the testing ground for Net-Zero development?

Lessons of History

When we think of the USA we may conjure up images of the iconic skylines of New York, Chicago and Los Angeles, the vast 6-lane free-ways and the suburban sprawl around every city, the industrialization of agriculture, its massive dams and canals, its nuclear reactors and electrical grid, its oil and gas production, refineries and distribution networks. Now consider this: China poured more concrete in a two-year period (2011-2013) than the USA did in the whole of the 20th Century [1].

Even given that China has a population three and a half times that of the USA, this is an astonishing statistic. It reflects the extraordinary pace at which China has played catch-up (and indeed surpassed) on its infrastructure. Concrete may be the bell-weather, but this trend is repeated across almost all resources and commodities.

It is tempting to suggest that China’s rapacious demand has been due to its role as the manufacturing centre for the world. Whilst this is partly true, these gargantuan amounts of concrete, steel and by extension – energy, have been flowing into infrastructure and not simply into consumer-goods for the West.

A useful illustration of this is the construction of Chinese railways. Twenty years ago, China had no high-speed rail lines, and the image of overcrowded trains slowly rattling along Mao-era rail lines was probably accurate. However, the build out of this critical infrastructure started in 2008 and only fifteen years later China has 26,000 miles (42,000 kilometers) of dedicated high-speed railways since 2008 and plans to top 43,000 miles (70,000 kilometers) by 2035.[2] According to The Economist in 2017, the reported 20,000 kilometres was already more than the rest of the world combined.[3]

The United States has just 375 miles of track cleared for operation at more than 100 mph (160km/hr).

Building railways, and indeed all infrastructure, is not an end in itself – but a fundamental part of development because infrastructure is a force-multiplier on economic activity. This is succinctly summarized in a Government of Canada report on “Role of Critical Infrastructure in National Prosperity”[4]

Well-designed infrastructure is an essential driver of national prosperity and is a prerequisite for economic expansion and for future growth to occur. Infrastructure enables a nation’s productivity, quality of life, and economic progression by driving growth, creating jobs, and improving productivity, quality of life and efficiency. It underpins growth by providing the supporting networks upon which we all rely.

Indeed, the Canadian transcontinental railway, completed in 1885, connected Eastern Canada to British Columbia and played an important role in the development of the nation.

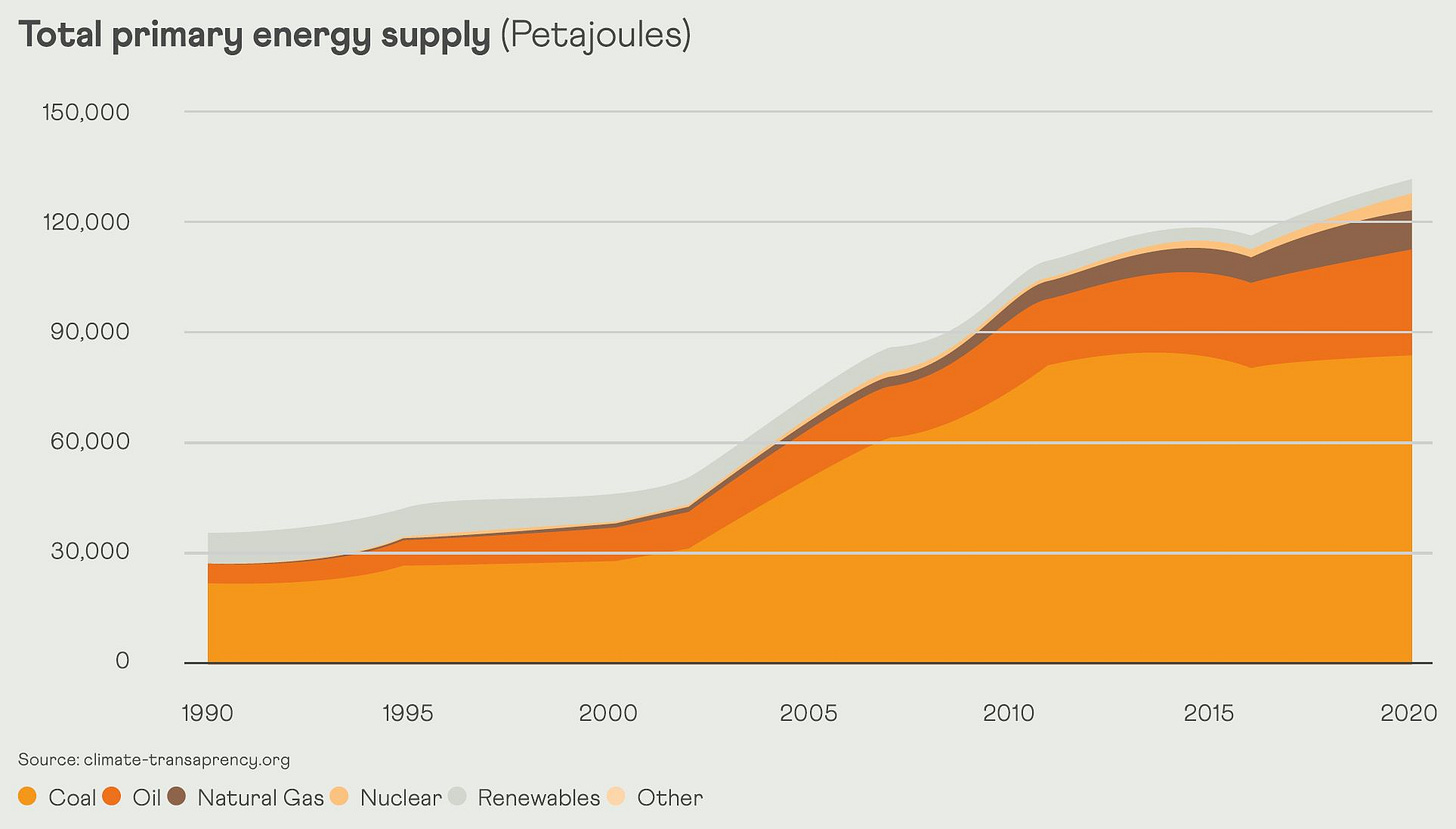

The rapid urbanization and industrialization in China have gone hand-in-glove with increasing energy demand. Whilst we hear a lot about China being a global leader in the installation of renewable energy, it is easy to see that the industrialization and development of China has required - in just the same way as it was for “Western” countries – vast amounts of energy supplied by coal, oil, gas, nuclear and hydro.

https://www.climate-transparency.org/04-china-energy-mix

Canada has its trans-continental railway that was finished in 1885, the USA has dams and interstates built in the 1930s-50s and nuclear power plants built in the 1960s and 1970s and Europe has infrastructure dating back to Roman times. The Golden Gate Bridge in San Francisco was built in 1933-38, The Hoover Dam in 1931-1935, the M1 Motorway in the UK was opened in 1959, the TGV high-speed railway connecting Paris to Marseille in France was originally built in the 1850s and upgraded to TGV specifications in the 1980s and 1990s.

It is easy to overlook how much current prosperity is predicated on this inherited infrastructure and the forgotten energy, and consequent carbon emissions, embedded therein.

Invested or “Sunk Carbon” is not a concept we ever think or hear about – but it is worth considering in the context of development and future carbon-budgets. Energy and resources are converted into infrastructure. The development of infrastructure has been a gradual process for most countries, but once done it means that a country benefits from deployed energy (and emitted carbon) that happened decades or even centuries ago. This provides a robust and resilient underpinning for a society and its economy but is easily undervalued.

Roadmap for Africa

As the world ramps-up its efforts to decarbonize, it is reasonable to question whether the energy transition roadmap for post-industrial Western nations should be applied to countries in development. Africa’s “energy transition” is one that should first and foremost lift people out of poverty. There is a moral obligation to at least not hinder Africa in its development. At the same time, we see an over-riding narrative that Africa’s development should be part of the global decarbonization effort. “Africa holds the key to accelerating global climate action. The continent doesn’t have an “old economy” that needs to be decarbonized. It can invest right away in the green economy that we need”[5]

As noted above with reference to the USA and China, rich countries have become wealthy from the enormous leverage of using hydrocarbons - the lesson we should draw from this history is that prosperous societies have been built on hydrocarbons.

However, the message to Africa is to ignore this lesson and to choose an unproven low-carbon developmental path.

Whilst Africa is a continent not a country, the parallels with China 30 years ago are still useful: a similar starting point of both having populations of 1 to 1.3 billion with a split towards rural locations, limited infrastructure and low individual energy use. There are also, however, many significant differences - not the least of which is the fact that the continent of Africa contains 54 independent countries vs. China being a single country under a tightly controlled administration.

Two significant differences that are of note are:

(1) The population of Africa is due to double to 2.4 billion by 2050, and by some estimates reach 4.2 billion by 2100[6]. Whereas, China’s population has been levelling-off over the last 30 years and is now shrinking.

(2) Africa has vast natural resources – traditional hydrocarbons, rich mineral concentrations as well as areas well suited to solar, wind, hydro and geothermal. Whilst China has some minerals and coal, as well as hydro, wind and solar potential, it is a major importer of oil, gas and minerals.

Given the lessons of late Twentieth-Century development from countries such as Korea, Japan and more recently China, it is impossible to imagine that the forces of population growth, industrialization and urbanization won’t come without a monumental call on concrete, steel, plastics and ammonia: the “Four Pillars of Civilization” as described by Vaclav Smil[7]. The inevitable requirement of these critical products implies an equally monumental increase in the need for energy.

The OECD, the UN, the World Bank and IMF as well as innumerable NGOs push Africa to not use hydrocarbons and focus only on “low carbon” energy. Such policy is predicated on an assumption that low-carbon energy is of equal value or utility. Whilst this is mostly true for hydroelectricity and geothermal – the critical developmental “Pillars of Civilization” needed for infrastructure and industrial development require more than just wind, solar and batteries.

By applying soft and hard (financial) pressure to only invest in low-carbon energy, wealthy countries are wilfully blind to the value of their own carbon-intensive legacy infrastructure.

Leapfrogging

The conundrum that is faced by Western activists, politicians, journalists and bankers is that by campaigning hard to “keep fossil-fuels in the ground” they are hurting the very people they are trying to help.

To side-step this inconvenient truth, we hear magical plans to help countries “leapfrog” from wood and charcoal direct to wind, solar and batteries, using the appealing, but flawed, analogy of how many countries skipped landlines moving directly to mobile telephones and e-payment systems.

Renewable energy can provide a fast and clean path to access to electricity which indisputably has enormous benefits to households and communities. However, “access to electricity” and industrialization are not the same thing. For the industrialization and urbanization of entire countries, access to robust dispatchable high-grade energy is fundamental. There are no examples of countries that have industrialized without a reliance on fossil-fuels, and for this reason many energy commentators believe that “leapfrogging” will not work. Given the uncertainties in exactly how a low-carbon development could work for 2 billion people, it seems reasonable to argue that Africa should not be used as a testing-ground for such an unproven thesis.

Indeed, there is no shortage of irony to be found in the difficulties faced by countries/regions leading decarbonization efforts. Germany is the poster-child with enormous expenditure leading to unintended consequences such as a return to coal, increasing energy prices and stubbornly high carbon emissions. So, whilst the wealthy G7-G20 countries hand out lessons in decarbonization, the wider group of “BRICS+” countries walk a different path. Security of energy-supply and affordability are paramount – which is usually effected by maintaining a reliance on legacy fuels driven by a focus on alleviating energy-poverty and general social-cohesion. Thus within a broader framework of development and energy-security, decarbonization becomes a secondary objective.

Carbon Justice

Given the foundational strength that wealthy countries have from their legacy carbon-intensive infrastructure, it is problematic to push Africa towards development using only low-carbon energy. There is, after all, the concept of a remaining Carbon Budget – that is, the amount of “permissible” carbon emissions being the difference between the number not to be exceeded to keep the planet on the modelled 1.5°C trajectory (2,890 Gigatons) and the cumulative human-derived emissions (2,479 Gt), resulting in a remaining “budget” of 411 Gt.

A study published in Scientific American[8] in 2023 showed how countries such as the USA have used more than their “fair share” of the Carbon Budget – and emphasized the importance of these over-consuming countries to rapidly ramp-down their emissions. Whilst that sounds good, it is clear that this remaining balance of 411 Gt can neither be respected, nor equitably distributed.

Despite its population size, Africa has contributed almost nothing to the historical carbon emissions. Thus, if Africa were to develop in a similar manner to China and use its “fair share” of the remaining Carbon Budget, this would imply that all other countries/regions would have to go to zero emissions (or even negative emissions) over-night to have any chance of meeting the global 1.5°C target. This is clearly not going to happen. By the logic of carbon-budget accounting, African countries will not even be able to use their “fair share” – given that countries who have “over-consumed” cannot reverse that position.

All this leads to a conundrum for Africa – subscribe to low-carbon development with a significant risk of slower development and less prosperity, or forge-ahead using all resources (both carbon-intensive and low-carbon) with a view to increasing wealth, prosperity and resilience? This latter point is not trivial – if Africa will be subject to more climate disruptions, as is often quoted (for example, Africa is one of the most vulnerable continents to climate change and climate variability, IPCC)[9], the best defence is wealth and the capacity for adaptation that wealth provides.

Keeping people poor is not a solution; energy poverty is poverty.

It is immoral to assume Africa should remain under-developed because other countries have developed earlier. The anti-fossil-fuel militancy aimed at Africa, whether it be from UN climate influencers, European activists or Wall Street banks, should be questioned, indeed it should be refused.

The Overton Window – a Window of Opportunity?

Two years ago, when I provided a macro-view for Savannah Energy’s 2020 Annual Report, the world was in a very different place. The global economy had had a decade of spectacular growth, predicated on ultra-cheap capital driving speculative markets in “tech” stocks and cryptocurrencies, from real businesses to Meme Stocks and the crazy NFT markets. At that time, the energy sector was like A Tale of Two Cities – “it was the best of times, it was the worst of times”. Renewable Energy and Climate Tech was booming, turbo charged by policies, subsidies and cheap capital. Legacy energy was suffering from low returns, expensive capital and public disdain.

In the decade 2010-2020 in the absence of war, pandemics, famines and shocked by excesses of the markets, citizens of the “developed” world looked for purpose. Campaigning for change was easy: you could occupy the moral high-ground and find your purpose, you could “make a difference”. Political decisions that would shape the economic direction of countries and indeed continents were being pushed by a (monolithic) argument: witness the phase-out of nuclear power in Germany in April 2023.

In this Brave New World there would be no place for fossil fuels (or nuclear), and indeed there would be no need for fossil fuels.

I believe the myopic view that carbon-dioxide emissions were the only problem facing humanity peaked at some point in 2019-2020. Since then, the complacent global order has been rocked by many obvious elements (pandemic, war in Ukraine etc). Less obvious has been the slow-burn of increasing energy insecurity.

From the summer of 2021 (pre-dating the war in Ukraine by at least six-months) Europe started to experience energy-cost issues leading to rapidly growing inflation in all countries.

Complacency was replaced by real hardship for many as energy costs ate into household budgets. In the UK for example, fuel-poverty has risen sharply and could affect as many as 8 million people[10] (although some estimates put this as high as potentially 2/3rds of all households[11]).

With families having to choose between “heat or eat” energy security and energy-affordability became headline material, and a Rubicon was crossed – the “Net Zero at any cost” is no longer a message that people want to hear[12]. The spread of ideas is rapid when people’s standard of living is impacted. This propagation is slower in the intellectual class who have made Net Zero part of their identity – this group includes asset managers, journalists, academics as well as politicians.

In Political Science this change in acceptable policy, or how policy has its moment, or zeitgeist, is called the Overton Window[13]. A policy window is never fixed, and like a pendulum, is now swinging (slowly) back from an extreme position, witnessed by the resurgence in positive attention to nuclear power (other than in Germany of course).

One would hope that a dose of energy reality in richer countries will lead to less dogmatic and more pragmatic efforts to support development in poorer countries.

A Just Transition

According to the UN, the population of Africa will double is by 2050 and possibly pass four billion by 2010. The right of billions of people to industrialize, to develop and to have jobs is being compromised by an over-emphasis on net-zero ambitions and the simplistic and unsupported assumption that low-carbon energy can simply displace high-carbon energy in the critical areas of concrete, steel, plastics and ammonia. This is the energy required to develop an industrial heart. Developed nations overlook the significance and value of their own legacy infrastructure and it’s “Sunk Carbon” emissions.

One can look at the energy-transition in Europe and North America as being anywhere from under-performing to delusional. However, there is a high degree of structural resilience due to infrastructure built using historical energy and its associated carbon emissions.

In the real-world, physics wins over platitudes and thermodynamics trumps arbitrary targets. The energy transition in developed countries is far from smooth: it is becoming increasingly expensive and will certainly not look like the green Utopia that is hoped for. Developing countries do not have the same starting point, there is no resilience based on legacy infrastructure, and will suffer if planned low-carbon development doesn’t perform as expected.

As the Green Utopian vision is replaced in OECD countries by a more practical and prosaic views on energy-security and affordability, so their willingness to support all energy projects in Africa, not just those that are low-carbon, should mature.

As Indira Gandhi eloquently stated in Stockholm as long ago as 1972, at what is recognized as the first global environmental conference:

“On the one hand the rich look askance at our continuing poverty--on the other, they warn us against their own methods. We do not wish to impoverish the environment any further and yet we cannot for a moment forget the grim poverty of large numbers of people.”

The Savannah Energy 2022 Annual Report can be found here - and has a fantastic section on “Why we do what we do” - investing in energy is Impact Investing.

[1] https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2015/03/24/how-china-used-more-cement-in-3-years-than-the-u-s-did-in-the-entire-20th-century/

[2] https://www.cnn.com/travel/article/high-speed-rail-us/index.html

[3] https://www.economist.com/china/2017/01/13/china-has-built-the-worlds-largest-bullet-train-network

[4] https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/cnt/rsrcs/pblctns/2016-rl-crtclnfrstrctr-ntnlprsprty/index-en.aspx

[5] https://climatechampions.unfccc.int/africas-role-in-decarbonizing-the-planet/

[6] UN data quoted by JHU https://saisreview.sais.jhu.edu/how-a-population-of-4-2-billion-could-impact-africa-by-2100-the-possible-economic-demographic-and-geopolitical-outcomes/

[7] Vaclav Smil How the World Really Works: A Scientist's Guide to Our Past, Present and Future Penguin, 2022, 325 p

[8] https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/wealthy-countries-have-blown-through-their-carbon-budgets/

[9] https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/02/ar4-wg2-chapter9-1.pdf

[10] https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-8730/

[11] https://www.theguardian.com/society/2022/aug/17/two-thirds-of-uk-families-could-be-in-fuel-poverty-by-january-research-finds

[12] https://www.uottawa.ca/research-innovation/positive-energy/publications/canadians-concerned-about-energy-prices

[13] ‘The Overton window is an approach to identifying the ideas that define the spectrum of acceptability of governmental policies. It says politicians can act only within the acceptable range. Shifting the Overton window involves proponents of policies outside the window persuading the public to expand the window.’